|

|

|

|

|

Peak Oil and Hybrid Cars

Dear Friends,

by Loren Cobb Have you test-driven a hybrid car recently? I recently had that experience at a Toyota dealership. You turn it on and there is only silence. You engage the motor, and the car silently moves forward. Enter a highway and step on the accelerator, and its small gasoline engine finally kicks in with an almost imperceptible vibration. Then comes the neatest trick of all: step on the brake pedal, and the electric motor turns itself into a generator, slowing the car by converting its substantial kinetic energy back into electricity. All the while the car is silent almost beyond belief. Turn on the stereo, and you have a wonderful listening experience, unlike any in all but the most expensive luxury automobile. I have to admit I was impressed, and not just by the 55 miles per gallon (23 km per liter) fuel efficiency rating. This experience led me to wonder how hybrid cars of the future may affect the pattern of energy use on the planet. Here are some thoughts.

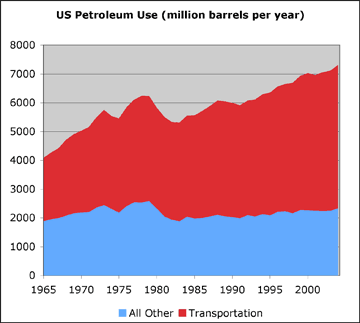

Peak OilThe "Peak Oil" hypothesis states that world oil production will attain an all-time maximum at some point in the very near future, perhaps between now and 2010, and that thereafter it will begin an inexorable decline. Though once highly controversial, this hypothesis has gained wide acceptance in recent years. There is no consensus, however, in the little matter of the consequences of this decline. There are now dozens of books and articles that outline various catastrophic scenarios that could follow from a transition in oil production from ever-growing to ever-declining. The core concept in these scenarios is that no replacement for petroleum can be found in time to avoid worldwide economic collapse, followed by massive starvation as petroleum-based agriculture also collapses. Having reviewed these analyses and predictions in great detail, I find the Peak Oil hypothesis extremely plausible, but the predicted catastrophe not at all likely. Hybrid automobiles play a key role in my analysis: they exemplify the kinds of substitutions that I believe will inevitably occur as the price of petroleum shoots upwards. I use the word "exemplify" here because I cannot predict exactly which product substitutions will actually occur, but I can confidently put forward hybrids as an example of the spectacular energy savings that can be achieved through market-driven changes in consumer behavior. Energy: The Big PictureThe economy of the world presently consumes energy at the rate of about 10.5 billion tonnes of oil-equivalent per year. Only 37% of this derives from oil itself; the rest comes from natural gas, coal, nuclear, and solar sources. Oil is unique in its ability to provide prodigious amounts of useful energy for very little cost. Peak Oil is of concern because no other source of energy has such a favorable a rate of energy output per unit of energy expended in the production process. The United States consumes about a quarter of the world's oil production, despite having only 5% of the world's population. If the USA can adapt to declining oil production, then the rest of the world will follow along with much less effort. If the USA cannot sufficiently adapt, then one of the Peak Oil catastrophe scenarios may actually become reality. The graphic above shows a breakdown of US petroleum use over the last four decades (data source: EIA). It is clear that transportation is the sector that has been responsible for almost all of our increased oil consumption. In all non-transportation sectors oil consumption hardly increased at all over four decades, even while the economy more than tripled in size. Transportation is also where the greatest waste of energy occurs, by far, and where the greatest progress can be made. Enter the Plug-in HybridThe gas-electric hybrid cars of today may seem advanced, but they still derive all of their energy from petroleum. Their performance can be improved with a very simple idea: plug them in at night, to be recharged from your home's electrical power. If the car's battery has enough capacity to cover at least one full day of commuting without a recharge, and if these batteries are neither too heavy nor too bulky nor too expensive, then a dramatically new vista of petroleum efficiency opens out before us. It is the batteries that are crucial for this. With a good enough battery, almost all of the power that you need for routine driving can come from the electric grid, which in most communities is not generated using oil. Power utilities vary, of course, but on average in the USA only 3.5% of the electricity which comes from a wall socket is generated by oil (source: EIA). This means that every plug-in hybrid car of the near future will save a tremendous amount of petroleum — exactly what we need to cope with Peak Oil — but only if battery technology can produce a high capacity battery at a reasonable price. The standard 2006 Toyota Prius comes with a battery that has enough capacity to drive only half a mile at highway speeds. If you replace this 1.3 kwh NiMH battery with a 9 kwh Lithium ion battery, then you would be able to drive 50 miles at commuting speeds before needing a charge. With this battery most of your driving will be powered from the electric grid, not petroleum, getting about 100 miles per gallon of gasoline. When the battery is drained then the car reverts back to normal Prius behavior, getting about 50 mpg (source: EDrive Systems). At $0.10 per kwh, the total cost of an overnight recharge will be under one dollar. The good news is that these high-capacity batteries exist today. The bad news is that they cost too much to be commercially viable at present. However, I predict that the combination of sharply rising gasoline prices and falling battery prices will transform this picture within five years, and that plug-in hybrids will become the dominant form of automotive transportation.

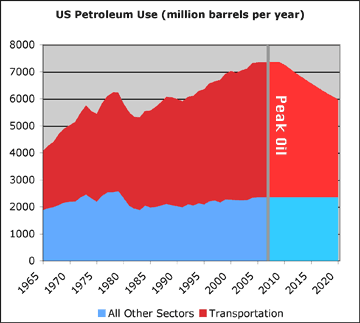

Long Term ImpactBetween the alarming instability in the Middle East and the ever-increasing price of gasoline, I think it is very likely that we will begin really needing the energy efficiencies offered by plug-in hybrids by 2012, if not sooner. If the technology is firmly in place and commercially viable at this point, then I anticipate that automobile customers will begin a massive shift over to the new plug-in vehicles. Within ten years after that almost our entire fleet will be running on electricity, causing a much-needed revolution in our use of petroleum. Of course such a massive substitution will place new demands on our electrical grid, but my calculations show that these demands will be surprisingly small. We can cover the entire amount of new demand for electricity by adding just 2 gigawatts of capacity each year between 2012 and 2022. Given that we already add between 20 and 50 gigawatts of new capacity every year, this additional burden does not seem in any way excessive. To see these calculations, click here. To summarize, by substituting plug-in hybrids for regular gasoline-powered cars the USA can cope with its full share of reductions in total petroleum consumption out to the year 2022. Doubtless many other substitutions will be inspired by skyrocketing oil prices, but this one stands out for its ability to provide extraordinary efficiencies without any change in governmental regulations or subsidies. If all newly purchased cars are plug-in hybrids after 2012, then the future of oil use in the USA may resemble the figure immediately above. With transportation efficiencies like this available, it is difficult to take seriously the fearful predictions of Peak Oil catastrophists. Make no mistake: energy prices will rise dramatically and life may become difficult as people struggle to become more energy-efficient. Nevertheless, I see no catastrophe looming over the horizon. Plug-in hybrids allow the ultimate source of most of the energy for transportation to be determined by power plants. At some point after 2025, when petroleum supplies are predicted to be dwindling rapidly, we may be able to achieve petroleum-free transportation through the use of ethanol-burning hybrid cars and an electricity generating system that relies on solar cells, wind and hydro power, nuclear power, and ethanol-based power plants. Sincerely your Friend, Loren Cobb

Readers' CommentsPlease send comments on this or any TQE, at any time. Selected comments will be appended to the appropriate letter as they are received. Please indicate in the subject line the number of the Letter to which you refer! Thanks for an excellent analysis of the problem. Does your 2012 year of "need" also assume a favorable cost-benefit to the consumer for buying a hybrid? Currently, the initial cost is not compelling from a purely economic point of view. Secondly, are there obvious government actions which could facilitate the switchover, e.g. "luxury taxes" on SUV's and/or high gasoline consumers, and reductions in oil company subsidies for that which they do anyway, like R & D and exploration? — Norval Reece, Newtown (PA) Friends Meeting.

I think shifting from liquid energy purchased from the anti-liberals who rule the major oil-exporting countries, to such sources as coal or nuclear (via electricity), is highly desireable. A cautionary note about the plug-in hybrid: a friend of mine who has done work for auto companies believes consumer resistance will be massive. Of course a steep price differential would work wonders. But oil from tar-sands, etc., might well come into play and be a major source for decades before a steep enough differential emerged. — Stephen Williams. You assume that your vehicles will be very light like the Prius, but already we have hybrid Ford Explorers and Honda Accords; won't they lessen your fuel savings? Of course, Honda has just taken the hybrid Honda Accord off the market for lack of demand, so perhaps the economics will be such that only very light hybrid vehicles will sell. You are very optimistic that further research will greatly increase the energy stored per unit of weight and drastically cut the cost per unit of storage of batteries. In view of all the research that has already been done on batteries by the major players, why are you so optimistic? You might mention that your battery research will be in competition with research to produce cheap ethanol from anything organic. It is not clear to me who will win, although of course both can; your plug-in car may have a motor that runs on ethanol rather than gasoline. Your plug-in car will be fine for day to day use, but when you want to put the family in the car and drive to your vacation at Yellowstone for two weeks, it will be awfully slow going with the backup motor of the size you seem to envisage for your plug-in car. Will we need to rent regular cars for longer multi-day trips? Finally, more electricity probably means more coal burned with global warming going with it, or more nuclear power with its radioactive disposal problems. Of course, you have demonstrated that your proposal for more electricity generation is only a small fraction of the total increase in electricity generation needed, so perhaps you are entitled to finesse the problem, and leave it up to those who are going to make the biggest increases in electricity generation. I have the feeling that other research will also be in competition with your research on plug-in cars, but I guess I am asking you to write a book, when all you want to do is stimulate our thoughts with a short piece, which you do successfully. — Bill Rhoads, Germantown (PA) Monthly Meeting.

Four questions:

— William Urban, Peoria-Galesburg MM.

Good article on hybrids. I just went through buying a car myself and saw a sign in the showroom saying that Toyota will have hybrid versions of all of their cards by (I think) 2012. A few observations from friends who have hybrid cars. My friends who have Priuses love them. On the flip side, one couple I know with a Civic hybrid didn't think it was worth the extra money they paid for it. First, you lose folding down the back seat because of where the battery is located. Second, it only gets about 5-10 mpg more than the regular Civic which is up around 40mpg on the highway to begin with. My main concern with them is towing capacity as I would eventually like a truck to tow a horse trailer with. As of now, the hybrid SUVs don't have enough power to tow anything but a small horse trailer and a small horse and I'd hesitate to use it to tow in really hilly areas. Hopefully in the coming years, more powerful hybrid engines will be produced that will have at least 10,000lbs of towing capacity. Personally, I think hybrids and alternative fuel vehicles will start to catch on in the coming years, especially as more models come out and gas prices continue to climb. I think they will become very common in areas like mine where people commute in heavy traffic for hours on end. Around here, commutes up to and over 50 miles and 1.5 hours are common. Already I'm seeing a trend towards smaller cars that get good gas mileage as it seems like all the car manufacturers have some sort of new sub-compact coming out this year. People want the roominess of the larger cars but the fuel economy of the smaller ones. My Scion xB is a prime example. It's built on the Toyota Echo platform but can easily fit 4 big people inside. — Deb Fuller, Alexandria Monthly Meeting, VA. You are right that hybrids could do much to offset the "oil shortage" in response to higher fuel prices. There is no reason that parking lots should not have coin-operated electric plug-ins, thus doubling the commuting/shopping range. However, the problem is not shortage of oil, but an excess supply of fossil fuels, leading to climate change. Climate change is a clear example of "market failure" since we are not charged for fossil carbon added to the atmosphere. Sure, the market will solve (almost) any problem, if it is given the right prices. Thus we urgently need a significant tax on all fossil fuels equivalent to $3 or $4 a gallon of gas. — Will Candler, Annapolis (MD) Friends Meeting. Thanks for this. My research agrees completely with yours. In addition I would add: I have compared the prices and mileage of the Ford Escape hybrid and standard models. This took a fair amount of study of various specifications to determine which trim packages were actually comparable, as the hybrid only comes in fairly high end dress, and as the performance of the hybrid, with a four cylinder engine plus an electric motor, is essentially comparable to the six cylinder conventional. (Electric motors have much better torque at low rpms, and consequently offer better acceleration.) The net result, even without federal and state tax breaks (which are currently both available to me) is that the hybrid's extra cost is paid for in 3 to 5 years at today's gasoline prices. (I for one don't think gasoline prices will remain this low for long.) You didn't mention that the liquid fuel component can be ethanol or biodiesel. Our capacity to produce these fuels is growing rapidly. In the end there is little that can be done with hydrocarbons that can't be done with carbohydrates. This means that food and fuel will be even more direct substitutes than they are now. Unfortunately, current agricultural methods are "mining" both fossil water and fossil soil — aquifers and topsoil that can't be replaced at the rate they are being depleted. It is not clear what the sustainable output will be when it stabilizes. Brazil has led the way here, though I have seen what sugar cane monoculture looks like, and I'm sure in the end it has environmental costs as well. I would be interested in your comment on the possibility of severance taxes on fossil resources (as opposed to the subsidies we now give to oil extraction). — Baird Brown.

With respect to the consequences of Peak Oil, correct predictions of disaster are rare. Successful predictions of disaster are common. When one dog barks, the others will join in, even if the first was barking at nothing. — Russ Nelson, St. Lawrence Valley (NY) Friends Meeting. I am neither an economist nor an engineer but I do own a hybrid, a Honda Civic, and am quite happy with it. I like the idea of highly-efficient, plug-in hybrid cars and the fact that they would not add much to current usage on the electric grid, but I have concerns about electric grid capacity now, what with "brownouts" during high-peak usage periods. Is this a legitimate concern or am I missing something? — Connie Brookes, Haddonfield (NJ) Friends Meeting.

My partner, Free Polazzo, has a loaded 2004 Prius which cost about $27,000 plus tax. His car averages 46 mpg. Nine months after Free bought his car, I bought an 2005 Honda Civic with the fewest number of add-ons you can get. My new Civic has all the amenities I need, including air-conditioning, automatic trans, and a full set of airbags. My car cost $13,300 plus tax. I now get 30 to 33 mpg in actual driving in both the city and on the highway, but it runs entirely on gas and therefore does create somewhat more pollution than the Prius, mile for mile. But since I drive one seventh the miles that Free does, my guess is that the actual pollution we create is similar. That was my tradeoff between cost, fuel efficiency and environmental concern. From an economic/environmental perspective, what do you think of my tradeoff? — Janet Minshall. I drive a 2003 Prius, and it gets about 42 mpg city but over 50 on the highway. I paid $23,000 for it, and Colorado gave me a tax credit which more or less equaled the sales tax. I really love this car, and now that I have had experience with it, I wouldn't mind if I had to plug it in. Before the Prius, plugging in a car seemed like too much to ask, so my expectations and openness to different car experiences have changed. — Ann Dixon, Boulder (CO) Friends Meeting. Thanks for your analysis of the Peak Oil issue, Loren. We have been satisfied Prius drivers for 20 months now, so I enjoyed your description of the possibility that hybrids might cushion the pain of high oil prices. In our experience, 45 to 48 mpg is about the best fuel economy we can achieve with any consistency, using an unmodified 2004 Prius. Since the Prius is lighter and more aerodynamic than most other designs, I am curious to know what mileage it would get with a conventional engine. Amory Lovins suggests that gas mileage could easily be doubled simply by reducing vehicle weight, and that avenue can be taken before battery technology improves. The people working on plug-in modifications tell us that even with a larger battery, once the Prius has accelerated, electric power alone can keep the car moving only at about 25 mph. But to get the vehicle up to speed and to cruise at speeds above about 25 mph, a petroleum-powered boost would be needed. So anyone who wants to use a plug-in Prius to avoid the gas station for long will need to change driving habits quite a bit. How many of us are willing to consider living someplace where we can walk to most of our destinations? — Steve Birdlebough, Redwood Forest Meeting, Santa Rosa, California. Your article's premise is that a single technology (or even a small set of technologies) can "save" us from the Peak Oil disaster. My main objection to this premise is that the prediction of a Peak Oil crash isn't based on the realities of the oil situation or any particular technology, but rather on the fact that our economic system is based on the assumption, heretofore accurate, of continuing increasing availability of cheap energy, particularly of liquid energy. If everybody were to behave rationally, the Peak Oil crash need not happen. The real threat, however, comes when bankers and investors begin to understand that most loans and investments are not increasing in value, but are in fact decreasing in value as growth begins to slow because of the lack of cheap energy (oil). Investment slows, loans begin to get called in, businesses default (happening already), runs begin (hasn’t happened much yet), the crash hits. This isn't going to happen simply and clearly, though I do believe it will snowball. There will be expansion of some businesses (the oil industry and related businesses will take off too, like alternative energy and high-efficiency battery companies), while more and more businesses won't start or won't expand because of the lack of cheap energy. We haven’t seen the significant decrease in growth yet, but it seems to me that there might be indications even in the current environment, and there is certainly talk about how high oil prices will have to get before they significantly impact the bulk of consumers and thus the overall economy. Currently they are only significantly impacting the poor and those on the edges of financial stability. One of your readers asked about what Europe was doing: they are certainly ahead of us. Sweden is putting a commission together to be free of oil dependence by 2020. See http://www.sweden.gov.se/sb/d/3212/a/51058. Some people are taking this seriously. I'm interested in others' thoughts. — Mark Inglis, Director of Technology, Denver School of Science and Technology.

My 4500 lb. 4x4 almost gets blown off the road by chip trucks here in Oregon. How would your plastic PHEV hold the road? — Webster.

Ho hum. When I was a kid in the 1950s, I worked for $1 an hour and bought gas for 20 cents per gallon. My car got about 10 mpg, so one hour of work took me 50 miles. Today, a kid gets about $6 an hour and pays $3/gallon. My car gets 25 mpg so an hour of work takes a kid 50 miles. — Jim Booth. [10 May 2006] Another good article, and I like hybrid cars. However, where does this leave alternative source of energy (e.g. ethanol derived from corn or sugar cane)? Brazil appears to have a success story with this new ingenuity by converting corn to ethanol. This year the U.S. ethanol industry will grow to provide more than 5 billion gallons of clean burning, renewable fuel to our country's supply. Ethanol's production drives economic development, adds value to agriculture, and moves our nation toward energy independence. Its use cleans our air and offers consumers a cost-effective choice at the pump. Moreover, countries like El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, and other sugar producing nations in the Caribbean and Latin America could easily meet the raw material demands for this fast growing industry. This would be a win-win story for all, and it would also add more value to the future of free trade agreements. Bottom line: we should not put all of our eggs into hybrid vehicles. — Mike Gonzalez, Miami, Florida. [12 May 2006]

One of your readers asked what the Europeans have done in response to their very expensive gasoline. The answer is that they have gone diesel. While gasoline and diesel fuel are about the same price in the USA, in Europe diesel fuel is less heavily taxed than gasoline, so it is cheaper. About half of all small cars made in Europe are diesel. I know there is controversy over getting low sulphur diesel fuel, and controversy over particulates from diesel engines, so I am not advocating diesel, just telling you what diesel can do. In September of 2003 I drove 2,300 miles in Belgium, Holland and France in the car that Hertz in Brussels gave me in response to my reservation of an ordinary small car — a Renault Megane 1.9 liter diesel with six speed transmission and air conditioning. In a mixture of city and country driving I got 45.5 miles per gallon. A Megane is slightly smaller than a Toyota Prius, and of course it has a stick shift, so it cannot quite equal the mileage of a Prius in an even competition, but it certainly is in the same league when it comes to mileage. Incidentally, I did not notice that I was driving a diesel car, as it equalled in all respects a gasoline fueled car. I think that in a one-on-one competition between a small hybrid and a small diesel, the hybrid would win, but I may be wrong, and I think you make a mistake in putting all your bets on the hybrid and ignoring diesel. It seems obvious to me that Europe will see a competition between the established diesel and the hybrid challenger, and I wonder which will win. Of course, if Europe continues to tax diesel fuel less per gallon than gasoline, it will not be a fair fight. — William Rhoads, Germantown (PA) Monthly Meeting. [12 May 2006]

I enjoyed your analysis to some extent, but I'm deeply concerned that you reach from an analysis of a single relatively easy substitute to a claim that:

Hybrid cars may well be one of the better options technology has to offer, and plug-in hybrids may be yet a further improvement, but I suspect that readers in Detroit and elsewhere may be less enthusiastic about your visions of a complete changeover by 2012. The infrastructure costs on the production side of such a changeover are very large, especially if conducted in a period when energy prices are increasing. Even if that relatively simple transition were to occur as smoothly as you predict, you ignore a large number of cases where substitution is more difficult, as well as some factors that reinforce energy issues outside of oil:

Finally, your analysis seems to assume a smooth transition over a fairly short time for markets and people to adapt. I sincerely hope that's the case, but given the turbulence in current oil markets, where increasing demand (from China, India, and elsewhere) is pushing against the limits of production, it's hard for me to see a smooth forecast ahead. You're correct that demand destruction will be critical to our facing the challenge of reduced oil supplies, but I find your forecast of how we'll manage that far too rosy. Perhaps it's as rosy as the catastrophists are catastrophic. — Simon St.Laurent, Attender, Ithaca Monthly Meeting (NY). [12 May 2006]

I would be most interested in any thoughts you may care to share on the future of coal and railroads. Especially considerting that the contribution of coal to global warming can be considerably reduced with smokestack washers and a limited use of bituminous coal. A two week vacation to yellowstone on a comfortable, high speed railcar such as the NY to DCA Metroliner could possibly exceed the pleasure level of two adults plus five children cooped up in an SUV. (Personally I would rather walk!) The expense of the rail tickets might be largely mitigated by the lack of enroute hotel charges and fuel costs. In New York City every block in the five boroughs is solidly ringed with cars day and night. If these millions are hybrid, each will require a frequent recharge. I believe it inpractical and most unlikely that the required infrastructure can be made available here (or in any large US city) during this century. (Think of the hell raised here about tearing up Second Avenue to provide one much needed additional subway — and this fight has been going on for about eighty years.) Other cities may also have this problem. As to the problem of a hybrid truck having insufficient power to haul a horse trailer — let the horse pull the truck! Semper Fi, — Bill Hibbs. Reply: The vast majority of commuters travel less than 60 miles per day, so they will require no additional infrastructure. Those that travel more are generally in vans and trucks, for business purposes. My essay addressed only passenger cars, and assumed that all other vehicles are not hybrids. With respect to coal, I expect that coal will be used for many decades to come, primarily to generate electricity in plants that are, as you suggest, equipped with effective pollution (and carbon) controls. — Loren The reason for my purchase of a 2004 Toyota Hybrid was for the clean air aspect of the car. A Pruis that travels from LA to NYC will produce less pollution than a typical gas powered lawn mower does in one hour. Sure, it's nice to saving money on gas. It's much nicer to be able to breath clean air. How much do the alternative fuels you mention pollute? Unless economists and accountants start talking about air pollution and healthy lungs, the focus will be on MPG and not on healthy living. How much is a set of healthy lungs valued by the "dismal science" these days? — Free Polazzo, Anneewakee Creek (GA) Worship Group, and Atlanta Friends Meeting. [30 May 2006] Just a comment on corn-based ethanol. This is not actually a very efficient way to manufacture ethanol. The yield is 1.6 units of energy out for 1 unit in (and the input is, in this country, mostly petroleum). Other methods of manufacturing ethanol, e.g., cellulosic or sugar cane, would be/are far more efficient (outputs of 10-20 times input). Brazil has been successful in producing mass quantities of ethanol because it uses sugar cane, not corn. Distillation is a major part of the energy input required to produce ethanol; with sugar cane ethanol, the energy required for distillation is derived by burning the sugar cane bagasse that remains after the juice is extracted from the cane. It's basically a self-sustaining operation with no net output of carbon dioxide. Corn-based ethanol would not even be economically viable were it not for the huge subsidies that the government gives to corn farmers, through direct subsidy as well as indirectly through tariffs on foreign ethanol. Basically, this is just one more way that the corn industry has invented to sop up the huge surpluses of corn that government agricultural policy has encouraged. — Bill Jefferys, Austin (TX) Monthly Meeting (now residing in Vermont). [1 June 2006] About the questions concerning the generation of electricity in the future: I saw a TV show recently, about undergraduate students from US technological universities who competed to engineer homes that used alternative fuels, mostly wind and sun. One prototype collected solar energy to run the home and had so much left over that the narrator discussed the selling by the homeowner of energy to the local power company! But in view of your article, that electricity could also be used to charge up the family's cars. I would like to see a big-picture analysis of all the alternative energy R&D going on at this time, and comments on how Peak Oil might affect the investments of those who will be retiring and depending on income other than social security. — Karie Firoozmand, Stony Run Monthly Meeting, Baltimore, Maryland. [27 June 2006] Why should we not simply advocate for small and extremely efficient cars? The hybrid technology strikes me as very complex, and as a Friend I seek simplicity. Ah, for the days of the old VW bug, when folks actually contemplated maintaining their own vehicles! Thanks for a comprehensive article. — Susan Jeffers, Ann Arbor (MI) Friends Meeting. [11 July 2006] Your article on plug-in hybrids is a very elegant solution to the wrong problem. The problem is not how to mitigate oil price increases after oil has doubled or tripled. The problem is how to avoid oil doubling or tripling. With our very high trade deficit and deep personal, corporate and government debt, we are much less prepared for an oil shock then we were in the 70s when the effects were disastrous. Toward this end we need massive government intervention now. Stop spending the money on Iraq and concentrate on subsidies for plug-in hybrids, public transportation, trains, etc. — David Israel. [12 July 2006] I fully agree with everything in the article on hybrid technology (TQE 145) except the last two lines on Page 2. Energy is not used across the country on a continuous basis. At night considerably less energy is used (which is why we made the switch to Daylight Savings time earlier this year). So in reality we need build no more power plants, because hybrids typically charge at night when the current power plants are running at less than 100% capacity. — Craig Shaffer, Hopkinton, MA. [22 Mar 2007] Found on the Web"I read every issue of Forbes, in order to get an idea of the worldview of the prototypical 'Rich Person' ... For the same reason, but in search of information about a very different worldview, I read The Quaker Economist, and am often astonished at what I find there. Sometimes I agree, sometimes I don't, but I always learn something. Unlike Forbes, it's free." — Ozarque, 8 Jan 2006. Book Notes

Bread of Dreams, by Piero Camporesi. University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Masthead

Copyright © 2006 by Loren Cobb. All rights reserved. Permission is hereby granted for non-commercial reproduction. |